Copyright © 2005 the Brewery History Society

|

Journal Home > Archive > Issue Contents > Brew. Hist., 118, pp. 2-20 |

The Trade in 1905 |

by Ray Anderson |

“The Trade” was a now outmoded collective label attached primarily to brewers and publicans, but often extended to hop and barley traders, brewery equipment manufactures, distillers, coopers, sugar manufacturers etc. to cover everyone with a commercial interest in alcoholic beverages. Both the members of the trade and its critics readily accepted the term. This paper examines the state of the trade one hundred years ago as reflected in the pages of journals devoted to its activities.

1904 had not been a good year for the brewers and 1905 would be no better. Beer production, already down by 7.0% on the turn of the century peak, would dip by another 2.5% during the year. Consumption per head would drop even more alarmingly, down nearly 15% on 1899. To make matters worse, there was a steady drift to cheaper beers on the one hand and to less profitable lighter bottled beers on the other. This was reflected in the inching down of average gravity by 3% between 1899 and 1905 to what today would be regarded as the still high figure of 1053.2.

It is a truism, as valid 100 years ago as it is today, that when things go badly for a company, the chairman will blame almost anything but himself. The 1905 annual general meetings of brewing companies, reports of which were carried in extenso in the trade press, contain many examples of chairmen trying to explain away their difficulties. Popular excuses were heavy beer duty (7s. 9d. (39p) per barrel), high taxation (income tax 5%) and the manner in which the Child Messenger Act of 1901 was administered. The latter prohibited the sale of intoxicants to children under the age of fourteen unless the beverage was in a sealed container; a restriction which publicans found irksome. A particularly chilling excuse for poor performance came from the chairman of the City of London Brewery, Robert Milburn. On 1st February 1905, faced with a sustained decline in profits to report at the company AGM, Milburn returned to his theme of the previous year1 when he had claimed that his brewery “had suffered considerably by the notorious alien immigration system, as they held a number of East End licences and the aliens had been the cause of driving the British workman further afield”. Now he blamed the “almost unrestricted importation of aliens” for his problems2. Whether the words flood and swamped were used is not recorded. Milburn welcomed the anticipated Aliens Bill which Arthur Balfour’s Conservative government would introduce later in 1905, and which would effectively stop the category of aliens he spoke of from coming to England. The aliens blamed by Milburn were Jews fleeing from the pogroms of Czar Nicholas II under whom the Russian’s treatment of the Jews turned from beatings to massacres in the early years of the 20th century. Of course, in the event, restricting the entry of refugees did not solve the problems of the City of London Brewery which continued to experience disappointing sales, as industrial prosperity declined in the Edwardian years, with falling incomes and growing unemployment - the major reasons for Milburn’s, and other brewers, problems. There was also heightened competition for the working man’s beer money from new sources of pleasure. At the 1905 AGM of Boddington’s Brewery held on 23rd February, a shareholder3, in moving a vote of thanks to the chairman noted that “there seemed to be a change coming over the beer trade. Instead of spending their money on beer, working men spent it on football and other things.” The chairman interjected to add: “And Hippodromes”. One can sense the puzzlement at the disloyalty of the labouring classes in turning their back on the national beverage in favour of such ephemeral attractions.

|

|

|

|

|

The number of persons licensed as brewers for sale was steadily decreasing as the century progressed, falling from 6,447 in 1900 to 5,491 in 1904. In 1905 the numbers dropped by a further 179. Over 85% of these closed breweries were very small affairs, producing less than 1,000 barrels a year4. Amongst the more substantial concerns to close their doors in 1905 was the Wood Yard Brewery of Watney, Combe, Reid & Co. Ltd, Long Acre, London, which had formerly been the brewery of Combe & Co. Ltd. There was also a bout of consolidation in Kent, with Style & Winch Ltd. of Maidstone purchasing the Sittingbourne Brewery of H.O. Vallance and the Style Place Brewery, Hadlow, together with some 60 pubs. Both breweries were promptly closed5. Notable takeovers during the year included Sydney Evershed Ltd., Bank Brewery, Burton-on-Trent by J. Marston, Thompson & Sons Ltd., with 86 pubs; the brewery survived until 1908. Some breweries went bankrupt, but reopened in a short space of time with new owners. Examples are the Burney’s New Cross Brewery Ltd., which was wound up early in the year, only to re-emerge as a new company, the New Cross Brewery Ltd.6, and the Rainton Brewery Company, East Rainton, near Sunderland, Co. Durham voluntarily wound up7, then within a month reopened as the North of England Clubs Brewery which had taken over the lease8. The latter in turn closed before the end of the decade.

A number of companies were having difficulties during the year but managed to fend off takeover or bankruptcy. A notable pair of companies in the latter category (who were only postponing the inevitable) were Ind Coope and Co. Ltd., and their Burton neighbours Samuel Allsopp and Sons Ltd., which were having a pretty miserable time of it in 1905. Both companies were suffering from poor management, past mistakes and falling sales. Such was the clamour of disgruntled shareholders that they had to issue a statement denying rumours that they were about to merge9. Many other breweries still managed a steady trade under sounder management and some passed into other hands in a healthy condition. A nice example is the Island Green Brewery in Wrexham with 21 licensed houses, which at auction in Birmingham, went for £73,600. Barrelage was quoted as 7500 a year and the auctioneer 10 noted that: “The brewery was established half a century ago, and had never before changed hands”.

The rush to incorporation amongst brewing companies had abated by 1905. All of the big fish had already become limited liability companies by then and only a few of the more modestly sized concerns remained as partnerships. A handful of the latter took the plunge in 1905, including two still familiar names. T & R Theakston Ltd., Masham was registered in March with a capital of £15,00011, and in October, Elgood & Sons Ltd., Wisbech, was registered with a capital of £50,00012. In both cases there was no public issue of shares and all of the initial directors came from the two families.

Building and extension of breweries had also slowed in the new century, mirroring the downturn in trade. But some companies continued to build, and splendid illustrations of some of these spanking new premises appeared as double page spreads in the Brewers’ Journal in 1905. Examples include: Webb Brothers and Co., Aberbeeg, Monmouthshire (now Gwent) with a new 15 quarter brewery; Ashton Gate Brewery, Bristol, with “new fermenting rooms, cooling, refrigeration, tank rooms, cellarage and copper house”; Phipps & Co. Ltd., new “fermenting house, copper house, cask washing yards, coopers shops, boiler house, smithy, dray sheds & etc.” installed at Northampton and the Albion Brewery, Mile End, of Mann, Crossman and Paulin Ltd., with an imposing block of buildings. The Brewing Trade Review, not to be entirely outdone by the Brewers’ Journal, published more modest illustrations of the new copper house of J.W. Green Ltd., Luton and the newly extended brewery of C. Hammerton & Co. Ltd., Stockwell. The extensions to the latter included a new covered cask washing yard, cooperage and workshops together with a new brewhouse and additional fermenting space.

Further afield, South African Breweries Ltd., Travenna Brewery, Pretoria the same name was given to Morgan’s Brewery Co. Ltd., of Port Elizabeth which was taken over by SAB in 1905). Ohlsson’s Cape Breweries Ltd, also built a new brewery in Johannesburg. A few maltsters and brewer maltsters extended their malting capacity during the year providing more material for the illustrator. Amongst companies confident enough to expand their operations were: Sandars & Co of Gainsborough with new maltings at Trafford Park on the banks of the Manchester Ship canal; F & G Smith Ltd., with new malt warehouse and offices at Wells, Norfolk; Morland & Co. Ltd., Abingdon, Berkshire with a new 100 quarter maltings built adjacent to their existing maltings which dated from 1716, and Nicholson & Sons’, Maidenhead, who had new malt and barley stores and new kilns added and the maltings “renovated and brought up to date, and fitted with the latest machinery, which is all electrically driven”. A rather different case of expansion was at Heriot-Watt College, Edinburgh, with the opening of a new bacteriological laboratory on 18th October 190513, when Emil Christian Hansen, the much revered head of the Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen, delivered a rather longwinded lecture on “Microbes and Industries”.

|

|

|

|

|

The May 1905 edition of the Brewers’ Journal carried a report14 under the headline “The Glasgow Fiasco” of what it called an “unpleasant illustration of the effects of total prohibition”. Under the terms of the recently passed Scottish Licensing Act magistrates had been empowered to close all public houses in a given area on a maximum of five days a year. The first day the magistrates of Glasgow chose was Easter Monday, with what was reported by the local press to have been “unexpected and unpleasant” results. The report went on: “Within the bonds of the city no liquor was procurable, and there was a stampede of thousands by rail and tramway to neighbouring places where drink was for sale. Paisley, which is seven miles from Glasgow, was thronged. A number of public-houses had sold out by the middle of the day, and others were so crowded that the proprietors had to close after a hopeless attempt to regulate the rush. A number of extra constables were called out to assist in keeping order.” The experiment was repeated on 10th July 1905 when this time the magistrates of Port Glasgow and Greenock chose the commencement of the annual holidays of the Clyde ship-builders to close all the pubs in the district. Again the results were reported in the press15: “The thirsty thousands, determined not to be beaten, took electric cars to Gourock, further down the Clyde, and from noon they struggled and tore at one another to gain admission to licensed premises”. The local police were reported to be “wholly unable to cope with the stream of men mad with thirst. Soon every green patch along the fine shores of Ashton was made the resting - place of helplessly drunken men and even women. Those who could still stand fought, in some cases, till their breath gave out. The quiet coasting place was a perfect pandemonium until two o’clock in the morning, when the constables were enabled to go to their homes”.

“Drunk” was the succinct description for the excessively inebriated for centuries. Samuel Pepys has this to say16 about the 17th century equivalent of today’s ladettes: “It was pretty to see how hard the women did work in the cannells sweeping of water; but then they would scold for drink and be as drunk as devils”. Now we have the clumsier term “binge drinker”. It is not just the terminology but also the circumstances that have changed. One hundred years ago communal heavy drinking in public and associated disorder went with a culture conditioned to hard manual labour and was usually constrained by cost to one night a week and bank holidays. Now neither of these factors appertains. Instead, with the initial encouragement and now the hand-wringing of local councils we have over-supply of cheap drink by rapacious retailers and cowed producers at the excessive number of on- and off-trade outlets. This has attracted a ready response from young people eager to shed their inhibitions through heavy consumption of deceptively strong drinks, bringing alcohol fuelled mayhem to Britain’s town centres with monotonous regularity. The only real historical parallel with today’s binge drinking shenanigans is the “gin craze”, which involved excessive drinking of the spirit in London between 1721 and 1751 and the associated strife and disorder depicted in Hogarth’s famous print “Gin Lane”. Then as now the trouble was abetted by shoddy licensing policies, cheap strong drink, over supply, too ready access and commercial pressures. Two actions which helped to kill the gin craze were more expensive licences and restriction on sales outlets. The emergence of a new beer, porter, may also have helped.

Edwardian attempts to combat drunkenness included efforts to curb sharp practices by the publican. In 1905 there continued to be much agitation about the widespread practice of the “Long Pull”, where as an inducement to continue his patronage of an establishment the drinker was served by the publican with a measure of beer greater than that he had asked for or indeed paid. Perhaps its modern counterpart is the “drink as much as you can for £10” and similar offers much beloved of the perpendicular drinking-sheds that litter our high streets, although such modern promotions are again closer to the gin craze and the apocryphal “drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence” notices rather than the comparatively benign inducements of the long pull. One of the more original ideas for discouraging the long pull came from the Oldham and District Licensed Victuallers’ Association with the suggestion that all beer should be sold by weight17. There were no takers. Not that such a move would have satisfied temperance movement which had its eyes on much more radical measures. But by 1905 the momentum of the temperance campaigners was on the wane and during May they suffered a triple blow in attempts to have the law changed to favour their ends. First there was the Scottish Local Veto Bill, brought forward with the intention that on a simple majority of electors local prohibition could be set up “so that no person within their area may keep for sale or disposal any kind of intoxicating liquor”. This bill 18 was defeated in the House of Commons on the second reading by 142 votes to 109 on 5th May. Then the English Sunday Closing Bill19, which aimed at securing total Sunday closing throughout England, was defeated in the Commons on second reading by the narrow margin of 114 votes to 108 after being unexpectedly debated late on the afternoon of Friday 26th May. Finally the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Earlier Closing Bill20 which would have allowed pubs to open for only one hour on Sunday and have them close at eight o’clock on Saturday night and at nine o’clock on week-days was defeated in the House of Lords by a mere 6 votes. It was all rather too close for comfort from the point of view of the trade but a welcome result none the less.

A major preoccupation of the brewing trade press during 1905 was the operation of the 1904 Licensing Act which allowed payments in compensation to the owners when a pub’s licence was extinguished other than for reasons of misconduct. The act was aimed at facilitating a reduction in the number of licensed houses by providing a cushion when a licence was removed from a pub. It had been welcomed by the trade and its workings during its first year were closely scrutinized. Summing up the results of some 520 cases21 the Brewers’ Journal was primarily concerned about inconsistency in evaluations, both in individual cases were different valuers arrived at different figures, and between cases, where no pattern could be discerned in the valuations: “In short, it is impossible to collect any principle from these cases …”.

An insight into attitudes towards the licensing trade in certain quarters in 1905 is given by a set of correspondence22 published in August’s Brewing Trade Review. The daughter of a Derby publican was expelled from her bible class when the occupation of her father was discovered, causing a not unexpectedly sharp exchange of views which drew in the girl’s father, the bible class superintendent, the vicar, the father’s trade association, the Bishop of Southwell and the Daily Telegraph. The latter took a very dim view of the incident calling it “a striking case of incomplete Christianity”, but the vicar remained unmoved.

By 1905, as the Brewers’ Journal noted23 “the ever increasing demand for bright, sparkling, light ale …. has been met with by many ingenious inventions”. One such invention from the USA was the “Wittemann Natural Fermentation Gas Conservation and Re-Saturation Process” in which “the carbon dioxide is collected from the fermenting beer, compressed, purified, stored at low temperature, and finally returned to the beer, which has meanwhile been chilled and filtered”. The process was “now in use in over one hundred breweries in America” and was “specially designed for top fermentation beers … and, we understand, that a complete installation is now being erected at Messrs. W. Butler & Co. Ltd., Springfield Brewery, Wolverhampton”. Although the gas was said to be “purified”, no attempt was made to remove fermentation volatiles, instead their presence in the recovered gas is made into a virtue, thus: “Since use is made of the natural fermentation gas, which is charged with valuable flavouring and aromatic properties, these latter are restored to the beer instead of being allowed to escape as in the ordinary system of fermentation”. The Brewing Trade Review was not entirely convinced of this when it reported24 first hand on the beer produced at Butlers. Whilst happy enough that all was well with the “rather heavy mild beer” characteristic of Butler’s ales, the journal “would have been glad of the opportunity of tasting a pale ale gassed from a pale ale fermentation”.

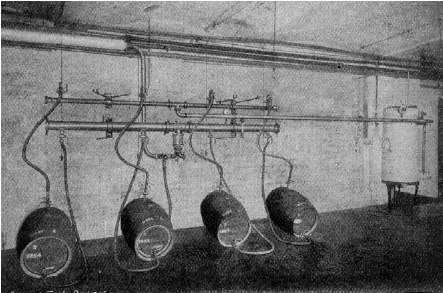

There was nothing particularly new in the Wittemann system. Originating in the USA, chilled, filtered, carbonated bottled beer, what was known as “nondeposit beer”, had been on the market in England since 189725, and the method had been widely adopted by 1905. Also, the collection and compression of fermentation carbon dioxide had been patented in the UK as long ago as 1892. But the application of chilling and filtering as described for the Wittemann process may well have created a first in the UK. It is clear from the descriptions given in the trade journals that it was intended that the process be used to produce not only bottled beer but also draught beer. The Journal of the Institute of Brewing carries a paper26 by the consulting chemist Charles Henry Field given in London on 16th January 1905, which concludes with the passage: “The fact that this bottled (chilled and filtered) beer with all its drawbacks is in such demand, should surely convince brewers that improved methods are essential if the trade in draught beer is to be maintained, and that the first to produce such a beer should have no reasons to regret having done so”. The Brewing Trade Review reported in the October issue27 that Butler’s had decided “after several months experience of the Wittemann Process to further extend its application to an output of 2000 barrels per week”. Production of draught beer racked under counter pressure using the “Golden Gate Racker” is described in all reports as an integral part of the Wittemann process. Draught beers produced by the process were said to be “… brilliant to the last drop, and there are no bottoms, waste, or returns. Priming is not necessary. Draught beer is ready for consumption immediately it is racked and the cask reaches the publican’s stillage”. Apart from the fact that wooden casks rather than metal containers are used and the beer was not pasteurised (a satisfactory method for the bulk pasteurisation of beer was over 20 years in the future and its application on any scale another twenty years after that) this is undoubtedly a description of what was called keg beer when it was launched in the UK exactly 50 years later. The CO2 content of the Wittemann process beer may even have been closer to that of modern keg beer than traditional cask. As the Brewing Trade Review put it 24 “the Wittemann cask is practically a huge bottle of beer”, and Field 26 noted that beer from a Wittemann cask “can be readily bottled, as they are already saturated with the natural fermentation gas”.

|

|

|

|

|

But, whatever its virtues Wittemann beer never got very far in the UK. It would seem that the British public were not happy with it. William Francis Wilson28, chairman of Butlers, looking back from the vantage point of 1912 is recorded to have made the following comments “… he had been interested in the carbonic acid gas method of raising beer for a number of years. His firm were using it in Wolverhampton at three or four houses 7 years ago. The beer looked and tasted well … everything went well, only (and this was the fatal objection) the public did not like it ... Black Country customers had strong likes and dislikes, they were very conservative, and if they would not have the beer there was an end of it”. One suspects that the added complexity, relatively high cost and limited stability of the beer - although Field claimed that such beer “will stand some 3-4 weeks or longer on draught” - were important factors. Nonetheless it is chastening to note that 2005 marks the 100th anniversary of the introduction of “keg ale” in England - albeit abortive. I wonder if CAMRA would have approved of the Edwardian version? After all, the beer was not pasteurised, the CO2 used to pressurise the casks was “natural” and the casks themselves were made of wood!

Certainly there was a ground swell of opinion that something had to be done about the beer on offer in the trade in 1905. In a passage29 which says much of the standard of Edwardian pubs, the Brewers’ Journal waxed lyrical on the potential for applying the process of chilling and filtration to cask beer: “The difference between the beer as existing in the sample cellar of the brewer, and the same article as drawn by suction for the consumer, is wellknown, and although endless attempts have been made to improve matters we cannot say that any very obvious success has resulted”. The nectar to come was eagerly looked forward to “… the article is sure to come, that is, a good-flavoured beer, chilled, filtered, carbonated, racked into enamelled casks, and eventually raised under gas pressure. The fluid, if not so profitable, would assuredly do credit both to producer and retailer, and the future will undoubtedly find such beer in actual being”.

If the Edwardian British public was steadily moving towards a preference for light sparkling non-deposit bottled ale, a few enterprising (foolhardy some said) brewers reasoned that it could only be a matter of time before they embraced the type of beer which had by then become the favourite with the rest of the world’s beer drinking classes. A couple of trade marks (illustrated) published early in 1905 show two of the lagers on offer. Wrexham lager had been going since the 1880s and was to prosper for another ninety odd years. Fremlin’s lager had a somewhat shorter life. Despite what it says on the Fremlin’s label, one wonders about the claim to being brewed “on the continental system”. The Wrexham brewery’s credentials were impeccable, having been built to produce lager, but one doubts that the few ale breweries which turned out a lager at this time actually installed the appropriate kit or used the right materials. Certainly reports30 that “Essence of Lager Beer” had been imported from Germany raises one’s suspicions. As the Brewers’ Journal rather slyly implied while putting the blame firmly on Germany viz: “This latest product of German ingenuity may, we imagine, come as a novelty to brewers in this country, though we have of course heard of somewhat similar concoctions, but it has remained for our neighbours of the Fatherland to discover the wonderful secret of exporting their national beverage in this concentrated from”.

|

|

|

|

|

The Brewers’ Journal might scoff, but it was in Germany that the first steps to an understanding of beer flavour were coming. Early in 1905 the German chemist F. Ehrlich showed31 that the “two amyl alcohols of fusel oil are derived from leucine and isoleucine”. The link to yeast amino acid metabolism was subsequently confirmed by others and Ehrlich’s is arguably the first contribution to understanding the biochemistry of beer flavour. Closer to home and much to the relief of the trade, with memories still fresh of the arsenic in beer poisoning epidemic of 1900, reports 31 that the red rubber rings used on beer bottle stoppers caused appendicitis due to leaching of antimony were refuted in a paper published in the Lancet of 20th June 1905.

In January 1905, under the heading “Growth of Commercial Motor- Traction” the Brewers’ Journal carried the following passage32 taken from the Times: “It is estimated that there are in this country at the present time upwards of 2,000 vehicles, classed as automobiles, engaged in the furtherance of industrial pursuits. Ten years ago it was difficult to find one. A few years hence who shall prophesy how many there will be? Already it is a cheap saying that the day of the horse is doomed, and the veriest gossip flippantly foretells his ultimate total extinction. The grip of machinery is on men’s minds, and the romance of the old horse days has seemingly passed into oblivion. But, in reality, the day is yet far distant when the brewer’s dray and the butcher’s cart will invariably carry their own propelling power”. Despite this vote of confidence in the horse from “The Thunderer”, motorised transport continued to make inroads. In March a news item in the Brewers’ Journal33 recorded that “a motor-van, loaded with 60 dozen of wine, had on the 10th March, made a trial non-stop run from London to Brighton, in 3h. 45min.” At the end of June 1905 the Automobile Association was formed with the main purpose of helping motorists avoid the police speed traps which were becoming increasingly common. The speed limit was 20 miles an hour. Further evidence of the spread of motorised transport came with the report34 that “London Brewers employ close upon 100 motor wagons … and considerable additions are about to be made to that number. The average load on the motor trolley is 30 to 35 barrels. Messrs. Mann, Crossman and Paulin Ltd., hold the record with 12 machines ...”. Meanwhile the same issue of the Brewers’ Journal contained a report on the inquest on a “brewer’s carter” who “had fallen from his lorry while under the influence of drink, and been run over”. The report records that the Coroner “condemned the practice of brewers allowing their workpeople three pints of beer a day, and allowing carters drink at every public-house at which they delivered barrels”. The jury was still out on the relative merits of the internal combustion engine and steam power. The steam wagon although relatively slow and cumbersome could carry a greater and was very robust.

|

|

|

|

|

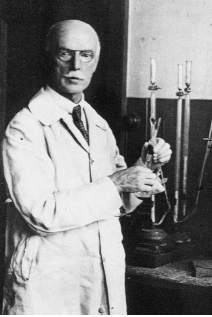

The first issue of the Journal of the Institute of Brewing for 1905 contains the text of a paper36 that had been presented at Brewers’ Hall, Addle Street, E.C.2 on 14th November 1904. It was entitled Zymase and alcoholic fermentation and it was by a chemist called Arthur Harden from the recently formed Lister Institute of Preventative Medicine. It is arguably the most significant paper ever to have been published in that journal which traces its history back to 1887 and is still going. The paper described the work of the author on the enzyme, zymase, discovered in yeast cells by the German scientist Eduard Buchner seven years earlier. This enzyme was claimed by Buchner to be responsible for the conversion of sugar into alcohol during fermentation. At first this was greeted with scepticism by the scientific community, but by the time of Harden’s paper was generally accepted. In his paper Harden announced that “zymase … needs the presence of another substance … to enable it to bring about its characteristic function”. He had found that when yeast juice (cell contents) was “dialysed under high pressure through a film of gelatine” he could obtain two fractions which independently had no effect on added glucose, but that when the fractions were combined he got fermentation of the glucose. He took the undialysable fraction to be zymase, the enzyme, and the dialysate to be a substance essential to the activity of the enzyme. These results came as a total surprise. Until then it had been taken for granted that zymase acted alone. At the time he gave his paper to the London Section of the Institute of Brewing Harden had no idea as to the nature of this substance. Shortly afterwards, however, he and his assistant William John Young found that both an organic cofactor, “cozymase” as it became known, and also inorganic phosphate were involved 37. Many years of work by Harden and numerous other workers were to follow before the significance of these observations became apparent with the unravelling of the pathway by which yeast turns sugar into ethanol. It was found that zymase was not one enzyme but twelve, that cozymase was a molecule now known as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and that phosphate was took part in a complex series of reactions involving the intermediates between glucose and ethanol and, through the so called energy rich compound adenosine triphosphate (ATP), was the driving force not just of yeast metabolism but of the metabolism of all living creatures. For his part in these momentous discoveries Harden was awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1929.

|

|

|

|

|

There was a long way to go but the vital clue is there in Harden’s 14th November 1904 paper delivered on a Friday evening to a group of brewers and brewers’ chemists. At the very time that his future Nobel Prize winner was still picking his way through his data, he communicated the results first hand to a brewing audience. What is more, the published version of the paper in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing is the first written account of any length concerning Harden’s crucial discovery of co-factors. He had in fact first communicated his results to the Physiological Society two days before he lectured to the brewers, but the only record of this account is a short one page notice in the proceedings of that society compared with the twelve page paper which appeared in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing. It may seem strange that such important work should find its way into an obscure brewing journal, but not perhaps that strange if we look at it from the position at the time. After all the paper was about alcoholic fermentation, the yeast Harden used came from a brewery and the Lister Institute largely existed through the generous endowment given to it by Rupert Cecil Guinness first Earl of Iveagh. Indeed the Institute had for a time run (not very successful) courses on the “industrial practice of fermentation” organised by a former Worthington chemist, George Harris Morris. Brewers’ chemists themselves were also still involved to an extent in main stream science. They were less prominent than had been the case in the 1880s, but had not yet slipped into the insular world they were increasingly to inhabit. Harden thus had ample contact with the brewing world. And, in truth, in 1904 Harden was far from the distinguished figure he was to become. Within a few months of his 40th birthday his career was in the doldrums, his position at the Lister was far from secure and he had until then contributed little to the literature. The Journal of the Institute of Brewing was indeed an obscure journal, but Harden was a fittingly obscure contributor to it, perhaps happy to be published wherever he could. All that was to change within a few years. In 1907 he was made head of the newly- formed “bio-chemical” department at the Lister. In 1909 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1912 he became Professor of Biochemistry at the University of London. As we have noted in 1929 he received a Nobel Prize (shared with von Euler). The Universities of Manchester, Liverpool and Athens conferred on him their honorary degrees. In 1935 he was awarded the Davy Medal of the Royal Society. He was knighted in 1936. Despite all this head-turning attention Harden, by all accounts a reserved, quiet, cautious man38 stayed in touch with the brewers. He contributed a further four papers to the Journal of the Institute of Brewing between 1910 and 1936, served on a number of the Institute’s committees and as an examiner through the 1920s and ‘30s, and lectured to pupil brewers at the Sir John Cass Technical Institute in Aldgate.

Of the hundred or so individuals who merited obituaries in the trade press during 1905, the following stand out: Two prominent brewers who died in the early months of the year were, William Joseph Buckley, on 19th January 1905 aged 53, chairman of Buckley’s Brewery Ltd., Llanelli and Charrington Nicholl, on 7th February 1905 aged 89, head of the eponymous Colchester brewery. Their obituaries show both men to have been typical of the country brewer of the time with as much attention to field sports as business. Buckley39 was “… a famous breeder of horses, one of the best judges of a horse in Wales”. A deputy lieutenant of Carmarthenshire he “hunted the county for 15 years entirely at his own expense …”. Charrington Nicholl40 showed even greater devotion to the chase “… in his younger days one of the hardest cross-country riders in Essex … for 45 years he hunted with the Essex and Suffolk Foxhounds”. A man of a different stamp who died in the spring was William Garton, on 8th March 1905 aged 73, pioneer brewing sugar manufacturer. His invert-sugar, for which he coined the name saccharum, made his fortune. He began brewing in Bristol in 1862 and bought the Anglo- Bavarian Brewery in Shepton Mallet in 1870, producing “light but full tasting beers of low alcoholic strength”. His obituary noted41 that “horticulture, music, and sculpture afforded his principal delight and his gallery of old and modern masters is probably one of the finest collections in the country”. Another substantial figure was Colonel William George Webb42, who died aged 63 on 14th June 1905, chairman of JW Cameron & Co. Ltd., West Hartlepool and of the North Worcestershire Breweries Ltd., Stourbridge, and a director of P Phipps & Co. Ltd. He was MP for Kingswinford, lived near Stourbridge, and left an estate of £592, 800 3s 0d, the highest recorded in any will detailed in the brewing trade press in 190543. Sir John Groves, who died on 2nd October 1905 aged 77, also merits a mention. Chairman of John Groves & Sons, Ltd., Hope Brewery, Weymouth, a business he built up and turned into a public company in 1895. He was also three times mayor of Weymouth and in 1900 was the last man to receive a knighthood at the hands of Queen Victoria44. The longest lived brewer to die in 1905 was William Beard on 11th December aged 94, partner for 57 years in Beards & Co, Lewes, Sussex45.

|

|

|

|

|

A number of brewers received honours during the year, amongst them the most elevated brewer of all time. The Brewers’ Journal for November 190546 recorded that Lord Iveagh, “whose munificence in the cause of charity and philanthropy is so well known” had been raised to a viscountcy. The noble gentleman, born Edward Cecil Guinness, actually enjoyed four titles in his lifetime, he was created baronet in 1885, was admitted to the United Kingdom peerage as first Baron Iveagh in 1891, advanced to a viscountcy in 1905 and an earldom in 1919. He was also invested a knight of St Patrick in 1895. In December three brewers were created baronets viz. Edward Mann a director of Mann, Crossman and Paulin, Ltd.; Richard P Cooper chairman of the City Brewery Co. Ltd., Lichfield and Herbert Praed one of the managing directors of Campbell, Praed & Co. Ltd., Wellingborough47. There were also two additions to prominent brewing dynasties in 1905. Although he was never involved in the family brewery, rather enjoying a part-time career as a novelist, poet and playwright, Bryan Walter Guinness (1905-1992) was a sixth generation descendent of the original Arthur and a grandson of the first Earl of Iveagh. He was destined to become the 2nd Baron Moyne in 1944 when his father was assassinated in Cairo by the Zionist Stern Gang. He also had the misfortune to be the first husband of Diana Mitford, who in 1936 married the British fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley. Bryan himself remarried in the same year and had an impressive record of fecundity, adding nine further children to the two he had by Diana. The other famous brewing name, or rather combination of names, to be perpetuated in 1905 was William McEwan Younger (1905-1992), who enjoyed a career in both politics and brewing, becoming the first chairman of Scottish & Newcastle Breweries Ltd in 1960.

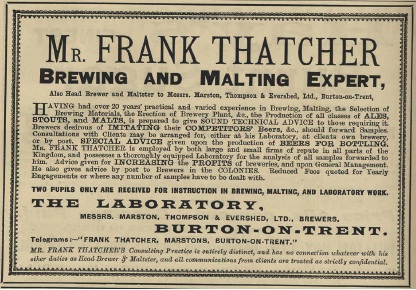

Two notable additions to the brewers’ library appeared in 1905. Reviewed in the March 1905 issue of Brewers’ Journal48 was Julian L Baker’s, The Brewing Industry. Written by the 32 year old recently appointed chief chemist to Watney, Combe, Reid & Co. Ltd., who would go on to be an influential figure in technical circles of the industry during his 46 years with the company, this little (170 page) book gives a succinct account for a lay audience of brewing as it was in Edwardian England. The May issue of Brewers’ Journal carried a review49 of Frank Thatcher’s, A Treatise of Practical Brewing and Malting. This hefty (560 page) rather verbose text book on brewing was written by the head brewer of Marston, Thompson & Evershed Ltd., who also doubled as a consultant.

|

|

|

|

|

On the 5th December 1905 Arthur Balfour, the Conservative prime minister, resigned with his party hopelessly split over tariff reform, and the Liberal leader Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman formed the new Government. The Brewers’ Journal lamented the departure from power of the brewing trade’s natural allies and greeted the new administration with heavy handed sarcasm50, “… the Government which gave us the Licensing Act of 1902, and the Compensation Act of 1904, was somewhat unexpectedly displaced by a Ministry for whom Home Rule, the destruction of voluntary schools, and the spoliation of licenceholders have lost none of their old charm”. So it was that the trade faced up to the New Year. It is perhaps as well that its members did not know what Lloyd George would have in store for them within a couple of years, or they may have become really depressed.

The Biochemical Society is thanked for permission to reproduce the photograph of Arthur Harden.

|

1. |

Brewers’ Journal. 40, February 1904, 90-91. |

|

2. |

Brewers’ Journal. 42, March 1905, 84; Brewing Trade Review. 19, March 1905, 176. |

|

3. |

Brewers’ Journal. 42, March 1905, 160-161. |

|

4. |

Brewers’ Almanac. 18, 1911, 157. |

|

5. |

Brewers’ Journal. 42, March 1905, 177. |

|

6. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, February 1904, 132, 199, 280, 607. |

|

7. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, June 1905, 403; Brewing Trade Review. 19, July 1905 418. |

|

8. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, July 1905, 438; Brewers’ Journal. 42, January 1906, 14. |

|

9. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, August 1905, 505. |

|

10. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, October 1905, 601. |

|

11. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, March 1905,169. |

|

12. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, October 1905, 607. |

|

13. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, November 1905 ,648-654. 654). |

|

14. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, May 1905, 287. |

|

15. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, July 1905, 411. |

|

16. |

The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Robert Latham & William Matthews editors. Volume 7, 6th September 1666, 278. Bell & Hayman Ltd: London. 1972. |

|

17. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, April 1905,255. |

|

18. |

Brewing Trade Review. 19, June 1905, 319. |

|

19. |

Brewing Trade Review. 19, June 1905, 320. |

|

20. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, June 1905, 348. |

|

21. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, December 1905, 717. |

|

22. |

Brewing Trade Review. 19, August 1905, 460-461. |

|

23. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, March 1905, 193-195. |

|

24. |

Brewing Trade Review. 19, October 1905, 557-558. |

|

25. |

Van Laer, N., “The Chilling and Filtering of Top-fermentation Beers”. Journal of the Federated Institutes of Brewing. 6, 1900, 439- 453, 440. |

|

26. |

Field, C. H., “The Chilling Process as applied to Draught and Bottle Beers”. Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 11. 1905, 107-122. |

|

27. |

Brewing Trade Review. 19, October 1905, 550. |

|

28. |

Wilson, W. R., Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 18, 1912, 419. |

|

29. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, July 1905, 456. |

|

30. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, April 1905,213. |

|

31. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, July 1905, 442. |

|

32. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, January 1905, 10. |

|

33. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, March 1905, 176. |

|

34. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, April 1905,255. 35. |

|

36. |

Harden, A., “Zymase and Alcoholic Fermentation”. Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 11, 1905, 2-15. |

|

37. |

Harden, A., & Young, W.J. “The alcoholic ferment of yeast-juice, II: The co-ferment of yeast juice”. Proceedings of the Royal. Society, 1906, N75:369-375. |

|

38. |

Hopkins, F. G. & Martin, C. J., “Arthur Harden”. Obituary Notices of the Royal Society. 4, 1942, 3-14.; Baker, J. L. & Robison, R., “Sir Arthur Harden”. Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 46, 1940, 295- 296. |

|

39. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, February 1905, 84. |

|

40. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, February 1905, 85. |

|

41. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, March 1905, 153. |

|

42. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, July 1905, 421; Brewing Trade Review. 19, July 1905, 418. |

|

43. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, November 1905, 657. |

|

44. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, October 1905, 605; Brewing Trade Review. 19, November 1905, 613. |

|

45. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, December 1905, 727. |

|

46. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, November 1905, 677. |

|

47. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, December 1905, 722. |

|

48. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, March 1905, 197. |

|

49. |

Brewers’ Journal. 41, May 1905, 337-338. |

|

50. |

Brewers’ Journal. 42, January 1906, 1. |