Copyright © 2004 the Brewery History Society

|

Journal Home > Archive > Issue Contents > Brew. Hist., 115, pp. 7-25 |

George Bateman and Son: Lincolnshire's last brewery. Part I |

by Steve Andrews |

My first visit to Bateman's brewery was in 1985 shortly after Martin Cullimore the present brewer had moved to Wainfleet. I had known Martin through my wife's work, so one day when we called in to see him he showed us around the brewery. It was like going back in time compared to the more modern breweries of today, with their high capacity and modern technology. I must admit I was impressed by its character and tradition. Shortly afterwards, the brewery was fighting for its existence when the brother and sister of the present chairman decided to withdraw their capital. After a two year struggle the business was saved, and it was still in the private hands of the same family. Having already become interested in the brewery, I had followed this struggle quite closely and it seemed quite unique in the present brewing industry for such a business to want to fight for survival and even more to actually succeed. What intrigued me most of all was that I realized Bateman's were the only surviving brewery in the whole of the old county of Lincolnshire, including what is now South Humberside.

When the subject for a dissertation arose I had the idea that I would like to trace the history of the Company with the intention of trying to find out why they survived as Lincolnshire's last brewers. I contacted Mr George Bateman through Martin Cullimore and was informed that they would be only too willing to let me go ahead and that they would give me as much help as possible. Fortunately for me there had been an exhibition on the brewery held in a local theatre in Boston to help promote the re-opening of Ridlingtons, the wine and spirit subsidiary of the company after their move to new premises. This exhibition had brought to light a lot material which had been locked away in an old laundry in the brewery for many years. This included various books, documents and maps, all of which gave me a starting point. Most of this material finished about 1920 and it included such things as cask books, which recorded the comings and goings of casks, so a trace could be kept on them and railway books which showed what had been sent and received by rail. There were also invoice books and petty cash books, but the problem with all of these was that they were incomprehensive and badly damaged, either by damp or mice. However, I did find they supported some of the details I was to get elsewhere. The most important source though that came out of the laundry were the letter books. There were six of these with something like 8,000 letters. Although they were mostly outgoing letters there were enough of them to make it possible to put together an impression of how the business worked during the First World War and in the few years preceding it. There was also a collection of incoming letters which matched up to some of the outgoing ones, but this was only very small.

I was told that I could have access to the Company's Minute Books, deeds or anything else that I might think was useful and I learnt that a couple of years before Mrs Pat Bateman, wife of the Chairman had tried to, put together a history of the Company herself and in doing so had interviewed a Mrs Burnett, who had worked at the brewery during World War One and the 1920s, and a Mr Mowbray a local farmer. The transcripts of both of these interviews were given to me. I did try to interview Mr Mowbray myself, but it was very difficult because of his age and I was unable to interview Mrs Burnett who was then in her nineties and living somewhere on the south coast.

My biggest problem was trying to gather together enough accounts to show how the company had progressed financially. This proved to be impossible because there were no comprehensive accounts to use. In the various Minute Books some form of annual statement is published, but this presentation varies too much to be of any use. I even wrote to Companies House to see what they had, but what they sent me on the microfiche only goes back to 1985. However, what was on the microfiche was the Memorandum of Agreement for when the business became incorporated in 1928. The only really useful figures I was able to put together concern the production of beer.

I also had several interviews with Mr Bateman himself who was been able to offer a great deal of information, particularly about the period in which he has been concerned with the brewery.

These have been my main primary sources. I also contacted the Brewery History Society and the Campaign for Real Ale for background information and used various secondary source materials for background into the brewing industry.

My method of approach to this work was to look at the progress of Bateman's and at the same time to look at what was happening to the industry nationally and regionally. This, I thought, would put Bateman's progress and their survival as the last brewers in Lincolnshire into some sort of context.

The nineteenth century saw many changes within the brewing industry, so to set the scene and the context into which the Bateman's Brewery was founded, requires a look into this historical background. Malt liquor had been the normal beverage of most people, strong beer or ale for adult men, table beer and small beer for family and servants. Brewing had been a domestic craft in many households but most people bought from a brewer.

It was a time when the majority of brewers were still only small scale and the majority of these were publican brewers, though there were many large scale specialist brewing companies, particularly in London, and Burton on Trent. However, the most underlying trend of the century was the decline of the small brewer and the gradual concentration of output by the bigger breweries (1) encouraged by increased mechanization, better transport and the ever increasing urban population. The following figures illustrate this trend:

| No. of Common Brewers | No. of Publican Brewers | |

| 1840 | 2,646 | 27,125 |

| 1890 | 2,330 | 6,350 |

Licensing Laws also had some effect on the ways breweries developed. From the 1830s Beer Duty was replaced by a duty on the raw materials, that is the malt and hops, and the breweries needed only to be open for inspection. This had come about because there was no accurate means of measuring the strength of the beer on which the duty was charged. Another Act of 1847 sanctioned the use of sugar (2). 1830 also saw the passing of the Beerhouse Act which allowed any householder assessed on the poor rates to procure a licence to retail beer on his own premises for two guineas a year. Magistrates had no power to withhold these licences as one purpose of this Act was to control the drinking of spirits.

However by 1869 the beerhouses were put back under the control of the magistrates due to the concern about the conditions of some of the houses and the problem of policing them. At this time there were 9,000 fully licensed public houses and 49,000 beerhouses in England and Wales (3).

The middle of the nineteenth century saw a large number of breweries in existence, the majority being small brew pubs, but with an underlying trend towards large specialist breweries. The following table shows how this had developed by the end of the century and the early part of the twentieth century:

| Brewers producing: | 1870 | 1890 | 1914 |

| less than 1,000 barrels | 6,506 | 9,936 | 2,536 |

| 1,000 – 10,000 | 1,809 | 1,447 | 580 |

| 10,000 – 20,000 | 210 | 274 | 197 |

| 20,000 – 100,000 | 128 | 255 | 280 |

| 100,000 – 500,00 | 23 | 34 | 46 |

| 500,000 – 1,000,000 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 1,000,000 - | 0 | 2 | 3 |

(4)

By 1880 Beer Duty had been reintroduced on the 'Free Mash Tun' policy, the duty being paid on the unfermented wort using a sacchrometer to measure the original gravity. The 1880's also saw breweries being floated on the Stock Exchange beginning with Guinness who were floated for £6 million. Brewery shares boomed which had the effect of increasing the prices of public houses as brewers competed for them in order to maintain and increase outlets to keep their shareholders happy. The tied-house system began to develop from this period onwards becoming one of the important features of the modern industry. At this time too many small breweries were being bought up so that their retail outlets could be acquired. Many of the big brewers began to merge and such companies as Watneys, Combe & Reid, Mitchells & Butler, and the Newcastle Brewery Company were formed, usually accompanied by a reconstruction of the breweries, concentrating on larger more efficient units.

It was also a period when more scientific methods were being applied to the manufacturing of beer. The introduction of the sacchrometer and the thermometer had enabled more control to be possible in the production of beer but some of the large brewers such as Guinness, Allsopp, and Ind Coope were employing scientists to examine their products and to analyse the reasons for bad beers or variations from normal quality. This helped bring about a more reliable product which would, in some cases, become the basis for national sales (5).

This sort of quality control helped bottled beers to develop from about the 1870s onwards though only on a small scale (6). All this led to an increase in the optimum size of a brewery as control of the process became more exact. At the same time improving transport systems were making market areas bigger.

The Temperance movement also exerted some influence on the industry resulting in the 1872 Licensing Act which had some effect on the hours of opening. This Act reinforced the powers of the magistrates to control licences and introduced the six day licence at a cheaper rate to the seven day and laid down severe penalties for the sale of adulterated liquor (7). The influence of the movement lasted well into the twentieth century causing much hostility between them and the brewers. The brewers eventually founded the Brewers Society to help unite against such opposition.

In Lincolnshire at this time we can see from Whites and then Kelley's Directories that the number of brewers in the county increased during the nineteenth century up to the 1880s then they start to decline again in line with what was happening nationally.

| 1826 | 43 |

| 1856 | 158 |

| 1872 | 181 |

| 1882 | 209 |

| 1892 | 135 |

The majority of them seem to be publican brewers, who very often had some other occupation as well, such as maltsters, farmers, coal merchants, corn merchants, Inland Revenue Officers, auctioneers. It is not until the 1872 Directory that specialist breweries seem to be appearing. One reason for the large number of brewers must have been poor transport facilities. Beer was a bulky product to transport and the market for any brewery by land carriage was only four to six miles, so each brewery could only serve a small area. As one of the main ingredients of beer is malt there were many maltings in the county, so much so that in 1853, in Lincoln, the Justices sought to reduce their number.

So this was the situation when George Bateman entered the industry. How and why he did so is part of the Brewery's and Wainfleet's folklore. I have come across the same story from various sources such as newspapers, local guides and commemorative articles. However I have also referred to the transcript of an interview between Mr and Mrs Bateman and Mr Mowbray (8).

Wainfleet had been an important medieval port, but from the end of the seventeenth century the Haven began to silt up, although in the nineteenth century traffic was still plying between Norfolk, Northern Europe. Salem Bridge (originally Sailholme) was as far as they came, barges then took the cargoes further inland (9). But as the sea continued to retreat Wainfleet's position as a port disappeared, mainly in favour of Boston, and the coming of the railways finally ended it. At the same time problems in farming were hitting the district adding to the town's economic decline.

|

|

|

|

|

The story of the brewery's beginning then, according to all sources, has George Bateman farming in Friskney. This can be confirmed in the 1872 Census in which George Bateman is listed as aged 27, living with his wife Susannah aged 24 and a servant Henry Bull aged 19. He farmed 42 acres and employed two people. However, like a great number of other farmers in the area he was having difficulties. The problems were mainly drainage and poor communications. He had taken out a mortgage on his farm, which Mr Mowbray thinks was College Farm, with an unscrupulous lawyer from Alford, who somehow cheated farmers over their mortgages forcing them to sell up. When this happened to George, he is supposed to have walked into Wainfleet to see if he could get hold of another farm. As he approached Salem Bridge he met 'Willie' Crow the owner of a local brewery. It is interesting to note here that Crow appears in various sources as Edwin, William or George T. and he or his father appear as brewers in the 1872, 1856 and probably the 1826 Directories though in the latter the name is recorded as Edwin Brow. Mr Mowbray says that when the two met George showed Crow the letter recalling the mortgage. Crow is then said to have suggested that George come into the Brewery with him as he wanted to retire. George said he knew nothing about brewing, was told to think about it and in any case Crow would teach him all he needed to know. He obviously took up Crows offer and went in to the business with him. This was probably in 1872 or 1873. By 1874 he was in a stage to buy 'Willie' Crow out and the original inventory puts this at £505 10 0. Unfortunately this inventory has disappeared but from a summary in another source (10) we can see that the brewery contained such things as a large brewing copper and cock with pulleys, draw damping iron bars for the fire flue, iron door and frame with brickwork tap and bottom two wood covers and all complete. There was also a small brewing copper of 220 gallons, mash tun, covers and iron false bottom. Hot liquor tub, copper hop strainer and mashing cratch, cast iron underback, two hot liquor pumps, pipes etc. and cold liquor pump, pipes etc.. Hop press screw tub, working round 300 gallons and various other items of equipment. It also lists such things as cow shed troughs, cucumber pit frame, gooseberry and currant trees, raspberry canes rhubarb herbs and things associated with the garden.

It has been written (11) that after a couple of years George bought the freehold to the brewery and then a few years later bought the present site. This is not true. After studying the deeds we find, in fact, that George bought the present site in 1876 for £800 taking out a mortgage of £543 18s 4d. In the following year we then find he bought the land that contained Crows brewery for £1,260 taking out a mortgage for £800. The documents relating to this reveal that Crow only rented the premises. So why George decided to buy new premises and then buy up the old brewery is not clear, but from the stone above the door of the present brewery it seems it was up and running by 1880. It has been suggested that the move came about because the land the old brewery was on was earmarked for the widening of the railway, but if this was the case the land was not compulsorily purchased until 1899. His new brewery was however still very close to the railway, and also to the main road between Boston and Skegness and his water supply from the Steeping River.

It appears then that George must have been doing quite well from the beginning to have been able to have bought out Crow and then to have bought the present brewery and the old one as well within a couple of years of each other. It is hard to discover whether he was an astute business man or luck just went his way. There were one or two factors that must have helped him on his way, the first being that the railways had come to Wainfleet improving the transport facilities available to him. Also a rival brewery at Wrangle owned by the Collins Brothers which was, according to Mr Mowbray, the main brewer in the area, went out of business after a couple of hot summers had dried up the pits from which they got their water. However Bateman's must have been reasonably established by this time because Collins did not go out of business until the 1890s. In fact they do not even appear in the directories until 1892 and they had gone by 1900. Another brewery in the area which was to close down at the end of the century was one at Old Leake owned by the Horton Brothers. This too closed because of poor water supplies (12).

When he began George Bateman possibly employed two workers and he owned one pub, the Black Horse at Thorpe Eudykes,(13) though I have found no written evidence to support this. In 1884 he bought the Chequers Inn at Croft and in 1898 he bought the Anchor Hotel at Friskney. It seems that his main markets were the local farmers who bought in beer for their own consumption and for their workers. It was delivered on his only dray in nine, twelve, fifteen, and eighteen gallon casks and according to Mr Mowbray was a very good 'pint' although the brewery would have been going some thirty odd years before he had his first taste.

|

|

|

|

|

When George began brewing in Wainfleet there are three other brewers recorded. One was W.H.Gunson who was also a wine and spirit merchant who gave up brewing at some stage but it is not clear when to concentrate on the wine and spirit side and they kept this business until it was bombed during the Second World War. Of the other two one at least was a brew pub being run by Edwin Eyres at The Barkham Arms which eventually became a Bateman's pub and I suspect the other brewer, a James Morley, also had a similar business. By 1892 neither Eyres nor Morley are recorded as still brewing.

As we saw in chapter one the floating of breweries on the Stock Exchange became the basis for a scramble for public houses and this expansion of tied estates was pretty remarkable. Breweries bid against each other doubling and trebling the prices of some houses. The number of on-licences fell from 104,792 in 1886 to 81,445 in 1914 whilst the population in the meantime increased by 44 per cent so small breweries were bought out to gain their trade (14).

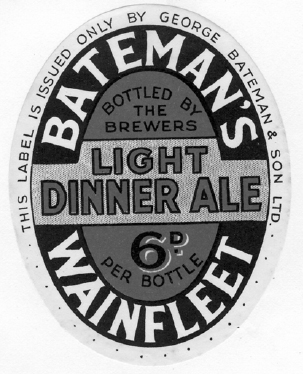

By the 1880s George must have established himself and we assume he must have been progressing quite comfortably and accumulating a small number of tied-houses or at least some guaranteed outlets. We do know from sources found in the laundry that much of his trade was to the private customer, mainly farmers. Mr Mowbray, who as a boy, remembers Bateman's bringing round the beer to the farmers on the horse drawn dray, says that they had two types of beer, a weaker one for the men and a strong one for the household. The earliest reference to beer prices appears in an Invoice Book for 1878 when beer was 6d a gallon. In April 1910 Ale was 1s 2d a gallon and bottled beer and stout was 1s 6d a gallon with 1s per barrel discount and 2d per bottle discount. Mrs Burnett, who worked in the Brewery offices, refers to one farmer called Joe Brambell who would buy a barrel for the six Irish labourers he regularly brought over at harvest time. The beer and the labourers would be closeted in the barn and they would always get drunk on Saturday night (15).

|

|

|

|

|

It has been the letter books that have given out the most information about the business, whilst it was under George's reign. The first letter that is readable is dated the 23rd March 1909 and addressed to the Shepherds Arms in Wrangle and refers to the fact that the law forbids children into rooms in licensed premises where intoxicating liquors are sold. Another early letter confirms that George had also acted as a wine and spirit merchant as he was applying to Messrs Mart & Co. in Finsbury to become sole agents for Encore whisky and later informs them that they are pushing the brand by sending out 400 leaflets.

We also learn in these early letters that they are trying to get into the supplying and running of outside bars and free houses. A letter to the Nottingham Catering Company on 25 October 1911 sees them asking to supply the Lincolnshire Show which was to be held in Skegness the following year. The letter extols the virtue of the beer's popularity; "We have been established in Wainfleet for 37 years and may say during the whole time our beers have enjoyed great popularity in the neighbourhood". There is also a letter to the General Manager of the Great Northern Railway in Kings Cross asking if they can supply beers to refreshment rooms. Another to a customer in Spilsby, presumably a pub offering them discounts on turnover. If this were to exceed £300 per annum, they will receive an extra 5 per cent -"this must be kept in the strictest confidence" (16). This sort of comment appears quite often.

Bateman's were also having dealings with some of the national brewers as early as 1910, if not before. There is a letter to Guinness in that year which confirms that they were bringing Guinness into the brewery and bottling it to sell in their own outlets and we find that they are buying it in hogsheads (17). In a letter of 1910 we learn also that they are bottling for Bass. In 1914 they were seeking to bottle for Worthington and in 1916 they were bottling for Thos. Salt & Co.

By the end of the nineteenth century the large breweries were setting up laboratories in order to analyse their beers and maintain quality control. Bateman's were too small to do this but they were using independent laboratories where samples were sent at various times to check the beer quality or the effect of new ingredients. The one they tended to use was Russells Bacteriological and Chemical Laboratory in London. One early letter to the laboratory gives us our first clue as to how George Bateman brewed his beer as he refers to "the mashing heat of 150f and after 20 minutes raised to 152f. The pitching heat was 150f and the original gravity 105" (18). I did come across some replies from Russells which indicate the types of reports that they would have written. For example in a letter dated 4 January 1918 it shows an analysis of some malt. The report reads:

" Brewers extract per 336 lbs 93.8lbs Tint of 20lb wort in 1 inch cell 23 Diastatic power(Lintner) 27 Moisture 3.1% This sample is passed as thoroughly well cured malt for the present day low gravity mild ales".

In these early years of the twentieth century the brewery did not have it own cooper and sent regularly to cooperages for men to come and repair casks at the brewery. Some of these requests went as far as Burton on Trent from where they also seemed to buy them. One company they dealt with in those days was the Kottingham Cooperage in Burton. Throughout the First World War they were forever suffering from a shortage of casks as they are continually trying to track them down and insisting on them being returned. It seems that they did not actually have a cooper even as late as 1920 when an advert is sent to the Lincolnshire Echo for one (19).

There are also references in the letter books that tell us they were running a bakery as part of the business. This was probably behind one of the cottages adjacent to the brewery, in what is now called Mill House. They seemed to have had the business for about seven years and in March 1911 they have advertised for a baker and are seeking references for an applicant. Whoever took the job on did not last long, because in the following year they are advertising the business for sale as "they are having to change our man and having an increasing business in our own line we cannot give it any attention" (20). This letter also says that the business will give a good living for an 'industrious' man and his wife and that there is accommodation in the shop and much potential for the business.

The biggest influence on the brewery during this period was the First World War and the restrictions imposed by government. For the first couple of years there is little correspondence to indicate any problems they might have been having but from late 1916 to the end of the war and even some time afterwards we get a good idea of what running a brewery during war time must have been like. The shortage problem was relatively straightforward as there were limits imposed on the amount of barley that could be produced for malting and the production of hops was restricted in favour of more necessary products. As for the legislation three particular Acts or Orders keep cropping up in the letters. These are the Central Control Board regulations, the Intoxicating Liquor Order and the Output of Beer (Restrictions) Act 1916.

I think at this stage we need again to have a look at what was happening nationally. Initially output fell by 35 per cent between August and December of 1914 (21). Prices rose because of increased duties and increased costs of raw materials. As the war progressed the output fell even further and beer was diluted. The Liberal Government had been hostile to the drink trade at the beginning of the war and allowed the military authorities and magistrates to impose local restrictions. By 1915 Lloyd George was so concerned with the drunkenness amongst the munitions workers that he advocated rigorous control over the trade.

In an amendment to the Defence of the Realm Act in May 1915 it was proposed to put higher duties on higher gravity beers, but after strong opposition from the Irish, notably Guinness, this proposal was dropped. There were calls for total prohibition and even nationalization of the industry. What in fact resulted from all of this was the creation of the Central Control Board in July 1915. In December 1915 the Board imposed in London, the Midlands, and parts of the North, licensing hours of two hours at midday and three hours 6pm-9pm in the evening. Throughout the war the Control Board kept a tight reign on the industry and there are many references to it in the Bateman's letter books. In July 1916 the Output of Beer (Restrictions) Act, restricted output to 15 per cent less than it had been for the year ending March 1916, in order to reduce land used for barley and hop growing. It also imposed a Compulsory Dilution Order. Penalties for contravening the Act were quite severe.

The Intoxicating Liquor Order which I have been unable to discover anything about, may have applied to the sales of alcoholic drinks and so therefore included the sale of spirits. Spirits, like beer, were rationed and restricted and were supplied on the quantities bought in during the corresponding quarters of previous years. It seems though that Bateman's had had a surplus in before the war which had lasted them until late 1916, the period during which, subsequent quotas were to be base. So when they wanted to buy in, during the second half of the war, their quotas were not as high as they would have wished. The sort of prices that were being recommended for spirits in 1916 were:

| Scotch | 29/- per bottle | 3d per tot (1/20th pt) |

| Irish | 29/-" " | 3d " " |

| Rum | 27/-" " | 3d " " |

| Pale Brandy | 30/-" " | 4d " " |

| Gin | 19/-" " | 3d " " |

| Special Whisky | 4d " " |

(22)

An example of how the Beer restrictions Act probably worked is revealed in a letter to the Bricklayers Arms, Friskney:

“It is obvious that you will be very short of beer before the 31st December, you only having 155 galls due to you. We trust you will see that the shortage is unavoidable and in no way blame us. If you turn to your books you will see that from April 1915 to December 30th 1915 we supplied you with 1572 galls of draught beer. We have been allowed to brew since April 1/3rd of the quantity we brewed in 1915. Likewise this is the proportion you will expect from us. Whereas we shall have supplied you with 1515 galls. We trust you will realize we are working under great difficulty and that we have done and intend to do what is best for you" (23).

It does seem from this letter that for some pubs they tried to increase the allocations, at the expense one assumes of private customers. For example a letter to a private customer, a farmer, says that he cannot be supplied unless he is threshing and then only with six gallons.

There were further Reduction Orders made, but not quite so effectively. It was planned in 1917 to reduce output to ten million standard barrels but it never worked. Strengths of beers though were effectively being reduced so that at one time they were down to 1036 degrees. As a result most of the big brewers made large profits during the war because their costs were so much less in terms of raw materials, though costs did rise somewhat in terms of duties. The biggest effect of the War was to put the trade much more under state control. Licensing Laws became more rigid, hours of sale were reduced, duties were raised and there was some nationalization of the industry (24).

|

|

|

|

|

Smaller brewers suffered much more as they had less scope for economies and less technical ability to adapt to new changes and many of them became prime targets for takeovers and it is probable that Bateman's struggled through most parts of the war period. However it does seem that Bateman's increased their free trade during the war, particularly to the working men's clubs in the Lincoln and Scunthorpe areas, which were heavily involved in the war effort. Some of the clubs were serving workers in war related industries, such as the steel works, the engineering industries and munitions, which meant they may have tried to get a special allowance of extra beer on top of their normal allocation and this would have meant the brewery could have brewed extra beer. If this is the case then it must have been of great value in helping to keep the brewery working. Mrs Burnett said "1916 to 1918 were the most difficult years but as soon as Harry Bateman got his licence to brew for the munitions workers in Scunthorpe and Frodingham more help had to be got in". I have not come across any written evidence to support any of this but I suspect it is true. Mrs Burnett goes on to say that the beer for the munitions workers had to be of a certain gravity and when it was ready it was siphoned off into special hogsheads labelled for the particular club it was going to. It is difficult to be certain as to the extent of this trade but from letters that went out to the various clubs it seems to have been quite extensive. We do know that Bateman's also got contracts to brew for the Navy and Army Canteen Board(25) which meant they could brew extra above their allotted allowance and this may also have applied to the Sergeants Mess of the 21st Lance Hussars based in Skegness.

Many of these clubs must have been new customers during the war, because the stewards did not always seem able to manage Bateman's beers. There are several complaints about the beer, coming from the stewards of these clubs as well as landlords of some of the pubs, who have taken on Bateman's beers and who are not used to serving it. Bateman's sent several letters to these customers and even sent representatives to help them sort out the problems. The sort of letter they were getting runs as follows;

"We ferment our beer in the old fashioned home brewed system and it requires rather different treatment to other beers. In case your steward should porous spile(26) either before tapping I think it would be better if he did not do so and that he did not spile until necessary to give vent" (27).

Another club was holding four weeks supply of beer which they are told is not a good idea as it should stand for no longer than two or three weeks. "The proper treatment is to stillage (28) on arrival, tap at the end of three days and after 24 hours of tapping it should be in nice condition" (29). Other reasons they give for the poor quality were the problems that were created by the war.

It seems that by the end of 1917 and into 1918 beer was in considerable short supply. There are many letters refusing new customers as they find it impossible to supply them. The contracts with the N.A.C.B. seemed to allow extra beer to be produced for the purpose of supplying them. An example of trying to get extra beer produced, comes in a letter to the Landlord of the Bell Hotel in Burgh le Marsh suggesting that he applies to the Canteen Committee or the Ministry of Food to get permission to have extra beer brewed as there are over 200 soldiers billeted in the area. Similarly an un-named club which asked them to brew extra beer is told that if they seek permission, they stand a better chance of getting it than if Bateman's applied.

We also see that the price of beer is being controlled to some extent. Initially in a letter in March 1917 we get prices being sent by the Licensed Victuallers Association. Then in a letter dated October 1917 the impression is prices are being controlled more centrally, presumably through the Central Control Board. The letter states:

"Beer must be sold on or after Monday October 29th at 5d per pint in at least one room in your house, if you have a smoke room or a snug in which it has been customary to charge more for the same quality of beer than in other part of the house you can continue to do so" The beer was being sold at 90/- a barrel with a 20 per cent discount. The letter goes on to say "there will be a great scarcity of beer this quarter and it will only be by our trade customers selling with discretion that we shall be able to keep all supplies" (30).

In another letter, which is warning them to be careful with their supplies because they are limited, gives the following advice:

"We particularly request our tenants to be most careful not to supply any person showing the least sign of intoxication nor to supply any customer with more than reasonable refreshment" (31).

It seems also that the brewery was allowed to brew extra beer at harvest time to make the traditional 'Harvest Ale', which was brewed for the farmers to give to their men whilst they were working but I suspect in 1917 and 1918 it was just an excuse to brew more beer to sell all round as there are one or two letters to the pubs explaining that there will be a little extra beer available. In 1917 it was being sold at 1/6d per gallon whereas normal beer was 2/6d a gallon, Harvest Ale being a weaker, lighter beer than the normal brew.

Because shortages were so great the brewery had at times to buy in from other breweries, particularly for the small brew pubs such as the Red Lion in Revesby and the New Inn in Boston who were both asked to supply pubs in their areas. Another example occurred in Surfleet where the Great Northern Hotel was being supplied by a Mr. Smith. However, the quality of the beers from these brew pubs was not always consistent and there were frequent complaints about the Red Lion's beer and about Mr Smith's beer.

The Beer Restrictions Act ruled that any pub that wanted to change its supplying brewery had to get hold of Bulk Barrelage Certificates which confirmed how much beer that particular pub had had from its previous supplier. The following letter is an enquiry as to the correct procedure for a particular case in which Bateman's seemed to have bought the lease.

"In 1915 a fully licensed house was sold. The licensee (although he had been absolutely free to purchase from where he chose) has obtained his supplies from one particular brewer. At April 6th 1916 there was a change in the tenancy and on April 1st1917 the new tenant asked the brewer for a certificate showing the bulk and standard barrelage in each of the four quarters of the year from April 1st1915 to March 31st1916 which was given and at April 1st1918 the house has been sold again and this time to a brewer. If he leaves the tenant free to purchase where he chooses we suppose it will be for the tenant to again request the certificate to be given, he could then transfer the barrelage to the owner of the property or will the brewer have to claim it" (32).

Sometimes a losing brewery was reluctant to give up the certificate. For example when a pub in Stallingborough wanted to be supplied by Bateman's, the landlord had problems getting his certificate off Norton and Turton the previous suppliers. There is also a letter from the Tower Brewery in Grimsby who say that they regret they cannot transfer a brewing certificate in respect of the Lion Hotel as they are brewing to capacity. However they do not object to Bateman's supplying the pub with any surplus beer.

A brewery could also give up part of its barrelage if it wished as Bateman's had to on one occasion, when they had been given a certificate by the Wellow brewery to brew 'Oatmeal Stout'. Because they were not in a position to brew it, presumably because they were brewing to capacity, Bateman's passed it on to Soulby's of Alford. This letter was towards the end of 1918 when Bateman's would have been brewing for the N.A.C.B. and the munitions workers. The amount was for only four and two-thirds of a standard barrel.

Shortages of raw materials were also a major problem. Malt and hops were in reduced supply for most of the war. One of the outcomes of this was to use invert sugar as a supplement to the malt. It was not until the end of 1918 that Bateman's are in a position where they need to use this. We find they are requesting five hundredweight of invert from Sugar and Malt Products Ltd Stratford, London and then following this up with a letter to Russells saying:

“we have received a small quantity of invert sugar. We are now mashing five sacks of malt at one time using four stone flaked maize and producing 28 barrels all at 10.22 gravity. We are not able to get flaked maize so must substitute invert sugar. Will you kindly inform as what quantity we shall require to substitute for stone flaked maize" (33).

We do actually have the reply to this inquiry from Russells and it reads like this:

"Flaked maize yields about 100 lbs extract or rather more per 336 lbs, while Invert sugar yields about 108 lbs per 336 lbs so that 1 lb Invert yields about the same - a trifle more - extract at the same weight of maize".

The letter also goes on to say that

"... the sugar should be used either in

- 1 in the copper

- 2 as a priming just before sending out

- 3 or in the copper and as a priming

If used in the copper it must be made sure that if it is in solid form it does not stick to the bottom of the copper and burn. If it sticks in the fermenting casks they must have their heads removed to clean them. All casks should be cleaned with boiling water to save the valuable sugar.

If used as a primer 1 quart per barrel of priming sugar will increase the O.G. by 1 degree, but the priming solution must be treated separately to the brew for Excise reasons".

There are also several letters to get licences and permits to purchase the sugar.

By the end of the war it seems that the majority of the beer being produced is very weak, an O.G. of 1022 according to the last letter, not just because of lack of materials, but greater quantities of weaker beers were allowed by the regulations. There are a series of letters written towards the end of 1918 and on into 1920 reflecting the quality of the beer. Some stating that despite the problems of the war, the beer is maintaining a good quality. However some customers had trouble with their beers at this time. There is a letter dated 22nd April 1919 from the Constitutional Club, Scunthorpe about the beer not clearing and being unpalatable. There is also a letter dated 15th March 1919 from the Crosby Road Club, again in Scunthorpe commenting on the fact that finings, which the brewery had supplied them, had cleared the beer and improved it so much that three barrels had been sold in one lunchtime.

With the ending of the war we find that Harry Bateman, George's son, has taken over as the driving force behind the brewery and it begins to expand and extra work is created. It was he, according to Mrs Burnett, who got the licence to brew for the munitions workers. It is also Harry that buys Ridlingtons of Boston in 1918 and in a letter to his accountants Hubbert, Durose, and Pain I think it shows that he is by then running the business;

"I have purchased a small Wine and Spirit business in Boston which has for many years been carried on by J.E. Ridlingtons & Sons. I intend to carry on under the same name and to keep it quite separate from my Wainfleet business" (34).

In 1919 he also bought Whorrams brewery at Burgh le Marsh along with all licences attached. He did not intend to brew from there, (it had closed before he bought it) but to use it as a bottle store and to sell and re-let the rest of the premises. He probably bought it for any tied houses that went with it.

The last real information in any depth we get from the letter books concerns a spell of poor quality beer which occurred in 1920 during the summer. At this time the customers were having trouble getting the beer to clear despite it leaving the brewery 'star brilliant'. There are many letters of complaint over the beer at this time so much so that the brewery issued a pro-forma to send to the customers so that any poor beer could be returned quickly. We get Harry travelling to Lincoln to reassure customers and presumably he went to other places as well. It seems also that other factors are adding to the problems such as transport delays. Casks are sometimes left waiting in railway sidings for over a day. It is ironic in one case because the Great Central Railway's Staff Dining Club at Immingham have found that their supplies are arriving late since the G.C.R. took over the deliveries from the Great Northern Railway. Other letters show that some landlords are keeping too much beer in stock or are storing the casks on their ends. The problems seemed to last until the end of August.

One of the things that Bateman's did to try and sort the problem out was to send a sample to Russells Laboratories along with a copy of the recipe:

Particulars of Brew

Foreign Malt 25% English Malt 70% Maize 5% 1cwt of invert sugar O.G. 54 Initial Heat 153f Tap heat 150f-153f Boil 2¼ hours Pitching heat 66f fermenting in square 20 hours then racked in trade casks at temp 72f gravity 37 and fermentation carried out to finish in trade casks (35)

I did not find any results from Russells but the beer rights itself at the end of August. One of the factors which they say might have caused it, was with the beer being so weak at the time, it did not clear properly. They also kept putting it down to the weather, which I assumed to be hot being as it was summer. Out of curiosity I got in touch with the Meteorological Office, who informed me that the summer of 1920 was in fact a poor one, cold and wet, and did not in fact brighten up until the October.

One interesting little aside at this point. I showed a copy of this recipe to the present brewer who was quite surprised and pleased because since he took over the position of brewer he has been working on the recipe to make it as pure as possible and he was quite delighted to see that his present recipe is not all that removed from this one of 1920.

|

(1) |

J Vaizey The Brewing Industry, 1886-1951 (1960) pp 3-17 |

|

(2) |

J Scarisbrick Beer Manual (Historical and Technical) (1896) Wolverhampton p 40 |

|

(3) |

JL Baker The Brewing Industry (1905) p 143 The Journal of the Brewery History Society |

|

(4) |

HS Corran A History of Brewing (1975) Newton Abbott pp 212-28 |

|

(5) |

Vaizey Brewing Industry p 4 |

|

(6) |

Corran History of Brewing pp 234-5 |

|

(7) |

ibid pp 265-72 |

|

(8) |

Transcript of conversation between G Bateman, P Bateman, and Mr Mowbray 16 Aug 1986 (hereafter Mr Mowbray) |

|

(9) |

Wainfleet A commemorative booklet for the quincentenary celebrations (1958) |

|

(10) |

‘Good Honest Ales, George Batemans & Son, Wainfleet’ Brewers Journal 20 Sept 1961 (Reprint) p 3 |

|

(11) |

ibid pp 3-4 |

|

(12) |

Interview with Mr Danby 21 Aug 1990 |

|

(13) |

Interview with George Bateman (hereafter G Bateman) 22 Aug 1990 |

|

(14) |

Vaizey p 20 |

|

(15) |

Transcript of conversation between P Bateman and Mrs Burnett 31 Aug 1986 (Hereafter Mrs Burnett) |

|

(16) |

Batemans Letter Books, 1909-1920 - 29 Nov 1920 (Hereafter LB with date) |

|

(17) |

54 gallon cask |

|

(18) |

LB 31 May 1910 |

|

(19) |

LB 23 Aug 1920 |

|

(20) |

LB 26 Feb 1912 |

|

(21) |

Vaizey p 20 |

|

(22) |

LB 18 Mar 1916 |

|

(23) |

LB 28 Nov 1917 |

|

(24) |

Vaizey p 25 |

|

(25) |

LB 21 Sept 1918 |

|

(26) |

A porous wooden peg which allows carbon-dioxide to escape from the cask |

|

(27) |

LB 11 May 1920 |

|

(28) |

Racking the casks in preparation to serving |

|

(29) |

LB 22 May 1920 |

|

(30) |

LB 27 Oct 1917 |

|

(31) |

LB 30 May 1918 |

|

(32) |

LB 7 Apr 1919 |

|

(33) |

LB 20 Nov 1918 |

|

(34) |

LB 1 Aug 1918 |

|

(35) |

LB 2 Jun 1920 |

In the next issue Steve Andrews discusses the company, its public houses and Harry Bateman.