Copyright © 2004 the Brewery History Society

|

Journal Home > Archive > Issue Contents > Brew. Hist., 115, pp. 2-6 |

James Joule – Brewer and Man of Science |

by Alan Gall |

William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin) and James Prescott Joule were good friends and scientific colleagues but probably not drinking partners. So when James wrote on 17th September 1853 that his family brewery had started a batch of Porter, he wasn't inviting Thomson to a booze-up. Far from it, the interest centred on the gas produced during fermentation not on the intoxicating qualities of the ale. They had already discovered that a temperature drop occurred when air expanded freely through a porous plug. Carbon dioxide gave an even better result – a reduction some four times greater than with air. The Joule-Thomson effect, as it became known, was one of the many manifestations of the equivalence of heat and energy that Joule made his life's work. The fact that heat could be converted to provide the work done by molecules in overcoming attractive forces paved the way for the liquefaction of gases and subsequent developments in low- temperature physics. Another famous scientist, Joseph Priestly (1733-1804), also made use of carbon dioxide when he conducted experiments at a brewery on Meadow Lane in Leeds. He may even have been the first person to propose artificially carbonated beer.

|

|

|

|

|

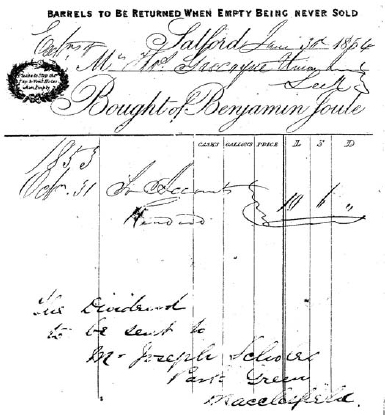

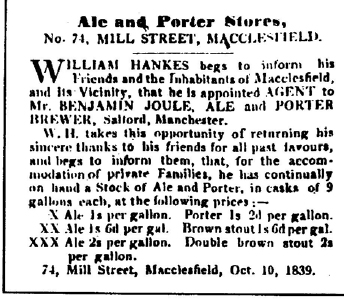

James Joule, son of Benjamin and Alice, came into the world on Christmas Eve 1818 at a house adjoining his father's brewery on New Bailey Street, Salford. James's grandfather had founded the brewery, which stood in the shadow of the New Bailey Prison, sometime shortly before 1788. Accounts from the Ring O'Bells, Didsbury, show that the pub served Joule's beer in 1791 when two barrels of strong beer cost three pounds and sixteen shillings. The brewery document reproduced on the following page carries the warning ‘Barrels to be returned when empty being never sold’. By the 1840s the brewery on New Bailey Street had about 13,000 barrels in use and sometimes a few went missing. This happened in June 1840 when Benjamin Joule supplied the Three Horse Shoes in the Old Shambles, Manchester.

The landlord of the pub, William Brierley, was a tenant of Sir Oswald Mosley and when Brierley fell into arrears with his rent, the bailiffs seized four barrels. These were subsequently sold, despite a warning by Joule's solicitor to the auctioneer that the matter would be taken further. And taken further it was – to the Lancashire Assizes at Liverpool. Joule won the case but lost on appeal.

|

|

|

|

|

James Joule had a small deformity of the spine, a condition that is said to have influenced his social skills in later life. Osborne Reynolds (the professor of engineering remembered for Reynolds Number) described Joule at age 51 as somewhat nervous and possessing no great facility of speech. The Joule boys had the advantage of a private education, taking lessons from no less a person than John Dalton the Atomist. Because of the wealth from the business, James was able to embark on a scientific career and indulge his passion for experimentation. According to one story, even on his honeymoon he carried a very accurate thermometer with which he measured the temperature difference between the top and bottom of a scenic waterfall. By exhaustive experimentation he established that chemical, electrical and mechanical energy could all be related by the amount of heat that was produced in doing work. One of his earliest results, now known as Joule's law, showed that the heat produced by a current (I) in an electrical circuit of resistance (R) is proportional to I2R per second. In his best-known experiments he determined the mechanical equivalent of heat by generating frictional heat with paddles rotating in various liquids. The SI unit of energy is justifiably named after Joule.

Some authors have suggested that James Joule had little to do with the running of the brewery but his letters to Kelvin do not support this idea. His scientific inclinations certainly led him to take an interest in the technical development of the brewery and during his father's illness he became heavily involved with the commercial side. When Benjamin Joule decided to retire, the task of selling the brewery fell to James. Two brothers called Thomas and Richard Smith showed a keen interest but subsequently caused James considerable annoyance by trying to drive down the price. There also seems to have been a problem with one of the employees. Writing to William Thomson in 1854 he complained that a Mr. Dix had reduced the brewery to a very bad condition and that ‘I have endeavoured to prove its real worth under proper management’. Father and son, John and Alexander Mills Dix, both worked at the brewery but John had died in 1842 so Dix junior is most likely the person to have been blamed for the brewery's poor performance. Later on, Alexander moved to the Stoke-on-Trent district where he set up Dix & Co at the Shelton Brewery, Hanley. A patent due to him whilst at Shelton, registered in 1868, covers a contraption for pumping a measure of finings into casks. A.M. Dix died in March 1883 leaving his sons, Alex and Harry, to run the brewery. Parker's Burslem Brewery Ltd acquired the company in 1921.

Negotiations continued between James Joule and the Smiths until eventually the brewery buildings and public houses were put up for auction. The sale notice for October 1855 reveals that the brewing equipment had already been removed and part of the site put to other uses. It was also specifically stated that whilst the buildings were suitable for manufacturing, they were not to be used for brewing. It may be that the Smith brothers bought just part of the site with an agreement to have this restriction in place. Certainly they are listed as brewers on New Bailey Street from 1855 to 1864. Edmund Crompton Batt appears at the Salford brewery in Slater's 1865 directory but by 1868 Ind Coope & Co and Robert Manders & Co (Dublin) were using the buildings as stores (the area was eventually redeveloped and the buildings opposite Salford Station now cover the site). The 1881 census places Edmund C. Batt as Manager at The Brewery, Highbridge Road, Burnham, Somerset.

|

|

|

|

|

A number of the pubs originally offered for sale in 1855 remained with the family for a time and 1872 licensing records show that ‘Dr. Joule’ was then the owner of the Albert, New Bailey Street, and the Old Kings Head, Chapel Street, Salford. The Old Kings Head had its licence transferred elsewhere in 1895 but the Albert lasted until the 1940s, as a Boddington's pub, until severely damaged during the blitz. What is perhaps the last remaining pub to have once served Joule's beer can still be visited in Manchester - originally called the Fleece, then the Kingston Hotel and finally Paddy's Goose, this stands on Bloom Street, opposite the coach station.

Another brewery existed in the area under the name of Joule. This was the Ardwick Bridge Brewery in Manchester run by James & William Joule. In all likelihood, these two were cousins of James Prescott. A family tree shown in Donald Cardwell's biography of Joule fails to show this particular branch but Benjamin Joule's Will, written in 1822, clearly indicates that it existed. The brewery at Ardwick Bridge, next to a dye works on the banks of the River Medlock, was first occupied by J. & W. Joule in about 1822. They remained there until about 1836, when only James is listed, and by 1838 the brewery was up for sale.

Alfred Barnard visited John Joule & Sons at Stone for volume three of his Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland (1889). There is no doubt that the Salford and Staffordshire Joules were related but genealogist Judith Marlow has cast doubt on the date for the foundation of the Stone brewery. Judith has constructed a comprehensive family tree on behalf of Daphne Joule who is James Prescott Joule's second cousin three times removed. According to Barnard, Francis Joule acquired the White Horse Inn and Brewhouse in 1758. Judith points out that Francis was then aged three.

On the 6th July 1854, James Joule wrote a rather sad letter to Thomson. ‘I have had much affliction here. My little Henry James died on the 20th day after his birth, and I have had, and still have, reason to be very much alarmed about my dear wife. She requires strength and does not rally properly. However, all that can be done has been done in the shape of advice. She and we have simply to resign ourselves into the hands of an all wise and ever compassionate Redeemer’. Amelia died two months later.

Following the death of his wife, James moved from his house in Acton Square, opposite to what is now Salford University, to live with his father at Whalley Range, Manchester. When Benjamin died in 1858, James bought property at Old Trafford but complaints from the neighbours about his experiments force him to move on. He next spent nine years at Cliff Point, Higher Broughton, Salford, before his final move to 12 Wardle Road at Sale, in Cheshire.

James Prescott Joule lived to be 70 years old although by 1878, when Queen Victoria had eventually granted him a special pension, his mental powers were on the wane. He died, after a long illness, on 11th October 1889. James is buried at the local cemetery and his headstone carries the number 772.55 – his experimentally determined value for the work required in ft lb to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one Fahrenheit degree.

I have consulted two biographies of James Joule given below. Additional material came from the Kelvin-Joule correspondence held at Glasgow University and for this I am indebted to Niki Pollock in the special collections library at the University of Glasgow. Further information about the brewery and Joule family has been collected from various sources; these include Wills, licensing records, census returns, and newspaper reports. Particular thanks are due to Judith Marlow, Tim Ashworth at Salford Local History Library and to Andrew Cunningham for the brewery receipt.

|

Cardwell, Donald S.L. James Joule – A biography (Manchester University Press, 1989) |

|

Reynolds, Osborne. Memoir of James Prescott Joule (Manchester Lit & Phil, 1892) |

Versions of this article have appeared in the February 2003 issue of Touch-Paper, the Open University Chemistry Society's newsletter, and Science Technology, the Journal of the Institute of Science Technology in November 2003.